Découvertes scientifiquesNos actifs 27/07/2020

Les 3 sources d’astaxanthine : laquelle choisir ?

L'astaxanthine est une molécule de la famille des caroténoïdes. Protection de la peau, santé des yeux, performances sportives, santé du cœur et fertilité sont autant des vertus largement étudiées dans la littérature scientifique. Son origine en revanche n’est pas toujours très claire : s’agit-il d’astaxanthine de sources naturelles ? D’astaxanthine de synthèse ? Ou encore d’astaxanthine produite à base de levure ?

Les interrogations entourant les sources de l’astaxanthine sont nombreuses. Et d’autant plus importantes quand il est question de choisir son complément alimentaire. Retour sur la récente recherche de Capelli, Tallbott et Ding pour faire le point.

Choisir son astaxanthine avec la science

Publiée en 2019 dans la revue scientifique Functional Foods in Health and Disease, la recherche de Capelli B., Talbott S. et Ding L. est une compilation de littérature sur l’astaxanthine [1]. Elle traite des 3 sources d’astaxanthine, de leurs différences chimiques et antioxydantes et de leurs bienfaits pour la santé. Cette recherche scientifique permet de mieux comprendre les provenances de cet antioxydant et de bien choisir sa source.

L’astaxanthine et ses 3 sources

Cette recherche a identifié 3 formes d’astaxanthine qui sont issues de sources différentes.

- L’astaxanthine naturelle est généralement extraite de l'hématocoque pluvial (Haematococcus pluvialis). L’Haematococcus pluvialis est une microalgue unicellulaire qui pousse dans l'eau douce et qui contient les plus grandes quantités d’astaxanthine.

- L’astaxanthine synthétique est produite à partir de produits pétrochimiques.

- L’astaxanthine de Phaffia est extraite de la levure Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous (Phaffia rhdozyma). Cette levure, qui produit naturellement de très petites quantités d’astaxanthine, a été génétiquement modifiée pour en produire de façon exponentielle.

Résultats de l’étude : laquelle choisir et pourquoi ?

Les trois formes d’astaxanthine présentent des différences au niveau chimique, de l’activité antioxydante et en termes de bienfaits pour la santé.

Les différences chimiques

L’astaxanthine naturelle, synthétique et de Phaffia se différencient par leur formule moléculaire et leur composition.

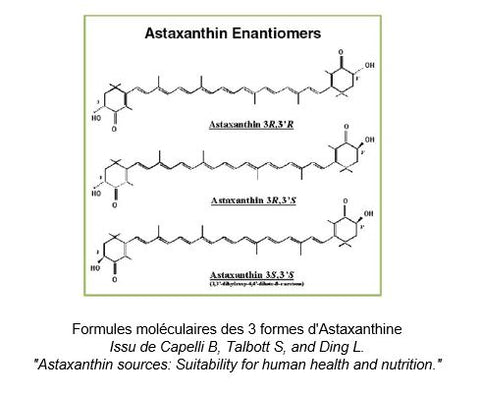

Leurs formules moléculaires ont des formes différentes (figure ci-dessous). Ces formes sont connues sous le nom d'énantiomères : l’énantiomère "S" (3S,3'S), l’énantiomère "R"(3R,3'R) l’énantiomère "méso" (3R,3'S). L’astaxanthine naturelle contient uniquement l’énantiomère "S" (3S,3'S). L’astaxanthine de synthèse contient une variété des trois énantiomères. L’astanxanthine de Phaffia contient exclusivement l’énantiomère "R"(3R,3'R).

Au niveau des différences dans leur composition, deux aspects sont à relever. Premièrement, l’astaxanthine naturelle est composée de 95,7 % de molécules estérifiées, ce qui n’est pas le cas de l’astaxanthine synthétique et de Phaffia qui sont « libres », soit non-estérifiées. Deuxièmement, l’astaxanthine de synthèse et de Phaffia ne contiennent pas d’autres caroténoïdes que l’astaxanthine. A l’inverse, l’astaxanthine naturelle est composée d'autres caroténoïdes, à savoir la cantaxanthine, le béta-carotène, la zéaxanthine et la lutéine.

Les différences d’activité antioxydante

En plus des différences chimiques, les auteurs ont aussi découvert des différences dans la force de l’activité antioxydante des formes d’astaxanthine. Sur la base de deux études in vitro, ils ont pu établir une activité antioxydante supérieure de l’astaxanthine naturelle à celle synthétique.

La première étude, publiée en 2013, a constaté que l’astaxanthine sous sa forme naturelle était au moins 14 fois plus puissant que celle de synthèse en termes d'activité antioxydante [2]. En outre, cette étude a testé l’effet des astaxanthines sur 5 radicaux libres présents dans le corps humain. Les résultats ont mis en évidence que l’astaxanthine naturelle était plus active pour éliminer l'oxygène singulet (jusqu’à 55x plus actif), l'ion superoxyde et les radicaux peroxyle, tandis que l’astaxanthine synthétique était plus active pour le peroxynitrite [2].

La seconde étude, publiée en 2015, a aussi mis en avant la capacité antioxydante supérieure de l’astaxanthine naturelle [3]. Dans cette étude, les chercheurs ont testé et comparé deux astaxanthines naturelles à une synthétique. Les deux formes naturelles avaient une activité antioxydante environ 90 fois plus forte que celle de l’astaxanthine synthétique [3].

Pour ce qui est de la comparaison avec l’astaxanthine de Phaffia, les chercheurs n’ont pas eu connaissance d’étude comparant l’astaxanthine de Phaffia aux autres formes. Cependant, puisque l’astaxanthine de Phaffia est chimiquement semblable à l’astaxanthine de synthèse, ils postulent que l’astaxanthine naturelle aurait également une activité antioxydante supérieure.

Innocuité et sécurité de consommation

Un autre aspect important est pointé par la recherche de Capelli, Talbott et Ding : l’innocuité. Ici encore, les trois formes d’astaxanthine présentent des différences.

L’astaxanthine naturelle a fait l’objet de plusieurs essais cliniques qui ont démontré son innocuité et une grande variété de bienfaits pour la santé. De plus, depuis plus de 20 ans, elle est consommée comme complément alimentaire sans avoir reporté d’effets indésirables.

En revanche, l’astaxanthine synthétique et de Phaffia n’ont pas été prouvées sûres pour la consommation humaine lors d’essais cliniques. C’est d’ailleurs pourquoi elles n’ont pas été autorisés par les organismes de réglementation gouvernementaux de nombreux pays.

Conclusion : quelle source d’astaxanthine choisir ?

D'après cette étude, l’astaxanthine naturelle semble être le meilleur choix pour vos compléments alimentaires.

En effet, la recherche réalisée par Capelli, Talbott et Ding a mis en évidence une activité antioxydante supérieure et une innocuité de l’astaxanthine naturelle. Tant que l’efficacité et l’innocuité de l’astaxanthine synthétique et de Phaffia n’auront pas été démontrées, les auteurs recommandent de choisir l’astaxanthine naturelle comme source de complément alimentaire.